Contents

- About Vocabug

- Interface

- Overall structure

- Categories

- Building words

- The alphabet directive

- The invisible directive

- The graphemes directive

- The stage directive

- The change

- Insertion and deletion

- The condition

- The exception

- Alternator and Optionalator

- Using categories

- Features

- Wildcards and quantifiers

- Cluster-field

- Advanced

- Blocks

- Questions and answers

1About Vocabug

This is the complete documentation for Vocabug, version 1.0.7. Vocabug randomly generates vocabulary from a given definition of graphemes and word patterns. It can be used to generate words for a fictional language, original nicknames or passwords, or just for fun.

This word generator is designed to be a successor to the Williams' Lexifer and to the legendary Awkwords. Vocabug is one of the applications belonging to The Conlangers Suite. You can also install Vocabug to be used in your own projects or as a command-line-interface here. If you would prefer a more typical user interface with simple syntax, please check out Vocabug-lite.

2Interface

- The textbox at the top of the program is the 'definition-build editor'. A definition-build defines the graphemes, frequencies, word-shapes and transforms that generate the final words. There will already be a default definition-build in the definition-build editor, or the previous definition-build that generated words

- Use the

Generatebutton to see Vocabug produce words. Yes, there are two generate buttons. - The button clears the definition-build editor and the generated words

- The and button will jump to the configuration and file save / load options, respectfully

- The generated words appear in a textbox below the editor

- Use the button to copy the generated words to the clipboard

- Use the button to download the generated words to your system

- The

Helpbutton shows this document - Below the copy words button is an 'output terminal'. It provides useful information about the generation run

2.1Options

Word-list modewill produce a list of wordsDebug modewill show, line by line, each step in creating each wordParagraph modewill produce words that look vaguely like sentences by injecting punctuation into the word list and capitalising the first word of each sentence- Use the

Number of wordstextbox to choose the number of words to generate. The default number is 100 - The

Dividertextbox sets the delimiter, or in other words, what the content will be between each word in the output. It is a space "\nto get one word for each line Remove duplicateswill make sure all words generated are uniqueForce wordswill force the generator to try and generate the complete number of words requested within 30 seconds, despite the number of rejections / duplicates removedSort wordssorts the words in alphabetical order, or the order defined in thealphabet:directiveEditor wrap lineswill make the definition-build editor jump to the next line if the line escapes the width of the definition-build editorShow keyboardwill reveal a 'keyboard', a character selector, below the options. Clicking on a character will insert that character into the editor- Use the buttons in the

Themesdropdown to change the colour theme of the editor

2.2File save / load

- Use the

Savebutton to download the definition-build as a file called 'vocabug.txt', or whatever you named your file in theFile name:field. The file is always a ".txt" type - Use the

Loadbutton to load a file from your system into the definition-build editor - Use the buttons in the

Examplesdropdown to load an example into the definition-build editor

3Overall structure

A definition-build is comprised of two top-level concepts: 'directives' and 'decorators'.

Directives are laid out like blocks and define the functions of Vocabug. The primary directives are the words directive, which creates each word, and the stage directive, which modifies each word with transforms. The other directives define concepts that are used by these primary directives.

Directives are written with their name on a newline, followed by a colon : on the same line, then followed by a newline. The payload after declaring a directive is interpreted according to the directive's semantics. A directive ends when a new directive begins, or when there are no more lines in the definition-build. For example:

words:example

Decorators change a property of a directive to modify the directive's behaviour.

Decorators start on a new line above the directive they are modifying with an at sign @, followed by the directive, a ., the property, optional whitespace, =, optional whitespace, and then the new value of the property. For example:

@words.distribution = flatwords:example

3.1Comments

If a line contains a semicolon ; everything after it on that line is ignored and not interpreted as syntax -- unless ; is escaped. You can use this to leave notes about what something does or why you made certain decisions.

3.2About graphemes

Graphemes are indivisible meaningful characters that make a generated word. Phonemes can be thought of as graphemes. If we use English words sky and shy as examples to illustrate this, sky is made up by the graphemes s + k + y, while shy is made up by sh + y.

3.3Escaping characters

A single-length character following the syntax character \ ignores any meaning it might have had in the generator, including backslashes themselves. This way, anything including capital letters that have already been defined as categories and brackets (but not whitespace) can be graphemes.

3.3.1Word creation character escape

These are the characters you must escape if you want to use them in categories, units and the words directive:

Reveal

| Characters | Meaning |

|---|---|

; |

Comment |

\ |

Escapes a character after it |

&[ and ] |

Named escape |

C, D, K, ... |

Any one-length capital letter can refer to a category |

< and > |

Evokes a unit |

, or |

Separates choices |

* |

Gives weight to an item |

{ and } |

Pick-one-set |

( and ) |

Optional-set |

[ and ] |

Supra-set item |

^ |

A null grapheme |

3.3.2Transform character escape

These are the characters you must escape if you want to use them in the stage directive:

Reveal

| Characters | Meaning |

|---|---|

; |

Comment |

\ |

Escapes a character after it |

<routine, = and > |

A routine is placed after the equals sign |

< and a space |

Begins a cluster-field |

&[ and ] |

Named escape |

>>, ->, =>, ⇒ or → |

Indicates change |

, or |

Separates choices |

{ and } |

Alternator-set |

( and ) |

Optionalator-set |

C, D, K, ... |

Any one-length capital letter can refer to a category |

[ and ] |

Feature matrix |

^ |

Insertion when in TARGET, deletion when in REPLACEMENT |

0 |

Rejects a word |

! or // |

An exception follows this character |

_ |

The underscore _ is a reference to the target |

# |

Word boundary |

$ |

Syllable boundary |

+ |

Quantifier, matches as 1 or more of the previous grapheme |

?[ and ] |

Bounded quantifier |

: |

Ditto-mark, duplicates the previous grapheme |

* |

Wildcard, matches exactly 1 of any grapheme |

%[ and ] |

Anythings-mark, matches 1 or more wildcards |

%[ and | and ] |

Anythings-mark with degrees or 'cowardliness' |

&T |

Target-mark |

&M |

Metathesis-mark |

&E |

Empty-mark |

&= |

Begins Reference-capture of a sequence of graphemes |

= and positive digit |

Reference-capture |

| A positive digit | Reference |

~ |

Based-mark |

3.4Named escape

Named escapes, enclosed in &[ and ] allow space and combining diacritics to be used without needing to insert these characters.

The supported characters are:

Reveal

| Escape Name | Unicode Character |

|---|---|

&[Space] |

|

&[Tab] |

|

&[Newline] |

|

&[Acute] |

◌́ |

&[DoubleAcute] |

◌̋ |

&[Grave] |

◌̀ |

&[DoubleGrave] |

◌̏ |

&[Circumflex] |

◌̂ |

&[Caron] |

◌̌ |

&[Breve] |

◌̆ |

&[BreveBelow] |

◌̮ |

&[InvertedBreve] |

◌̑ |

&[InvertedBreveBelow] |

◌̯ |

&[TildeAbove] |

◌̃ |

&[TildeBelow] |

◌̰ |

&[Macron] |

◌̄ |

&[MacronBelow] |

◌̠ |

&[MacronBelowStandalone] |

◌˗ |

&[Dot] |

◌̇ |

&[DotBelow] |

◌̣ |

&[Diaeresis] |

◌̈ |

&[DiaeresisBelow] |

◌̤ |

&[Ring] |

◌̊ |

&[RingBelow] |

◌̥ |

&[Horn] |

◌̛ |

&[Hook] |

◌̉ |

&[CommaAbove] |

◌̓ |

&[CommaBelow] |

◌̦ |

&[Cedilla] |

◌̧ |

&[Ogonek] |

◌̨ |

&[VerticalLineBelow] |

◌̩ |

&[VerticalLineAbove] |

◌̍ |

&[DoubleVerticalLineBelow] |

◌͈ |

&[PlusSignBelow] |

◌̟ |

&[PlusSignStandalone] |

◌˖ |

&[uptackBelow] |

◌̝ |

&[UpTackStandalone] |

◌˔ |

&[LeftTackBelow] |

◌̘ |

&[rightTackBelow] |

◌̙ |

&[DownTackBelow] |

◌̞ |

&[DownTackStandalone] |

◌˕ |

&[BridgeBelow] |

◌̪ |

&[BridgeAbove] |

◌͆ |

&[InvertedBridgeBelow] |

◌̺ |

&[SquareBelow] |

◌̻ |

&[SeagullBelow] |

◌̼ |

&[LeftBracketBelow] |

◌͉ |

If you are using this, you should be very interested in the Compose routine.

4Categories

Categories are declared inside the categories directive on a line each. A category is a set of graphemes with a key. The key is a singular-length capital letter. For example:

:C = t, n, k, m, ch, l, ꞌ, s, r, d, h, w, b, y, p, g F = n, l, ꞌ, t, k, r, p V = a, i, e, u, o

This creates three groups of graphemes. C is the group of all consonants, V is the group of all vowels, and F is the group of some of the consonants that will be used syllable finally.

These graphemes are separated by commas, however an alternative is to use spaces: C = t n k m ch l ꞌ s r d h w b y p g.

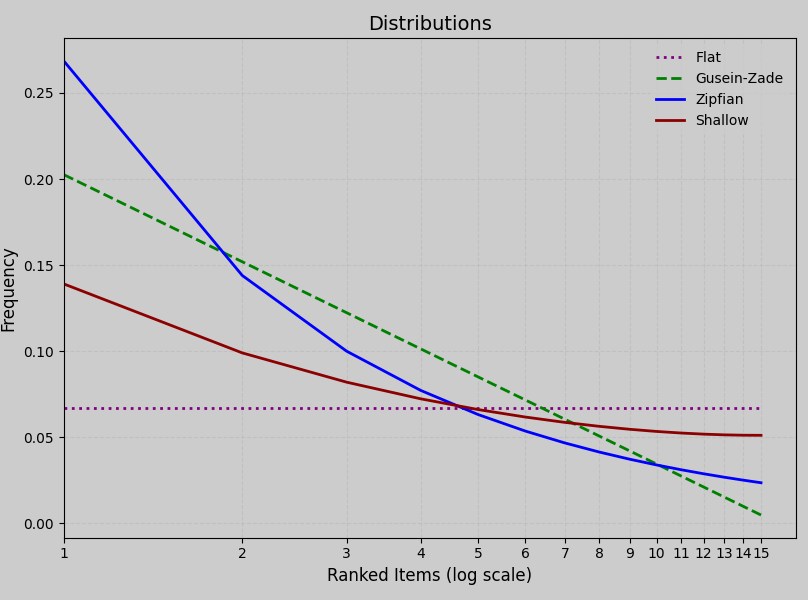

By default, the graphemes' frequencies decrease as they go to the right, according to the Gusein-Zade distribution. You can change this distribution with a decorator on the words directive, read how to do this here. In the above example, when Vocabug needs to choose a V, it will choose a the most at 43%, i the second-most at 26%, e the third-most at 17%, u the fourth-most at 10%, and o the fifth most at 4%.

Need more than 26 categories? The following additional characters can be used as the key of a category or unit: Á Ć É Ǵ Í Ḱ Ĺ Ḿ Ń Ó Ṕ Ŕ Ś Ú Ẃ Ý Ź À È Ì Ǹ Ò Ù Ẁ Ỳ Ǎ Č Ď Ě Ǧ Ȟ Ǐ Ǩ Ľ Ň Ǒ Ř Š Ť Ǔ Ž Ä Ë Ḧ Ï Ö Ü Ẅ Ẍ Ÿ Γ Δ Θ Λ Ξ Π Σ Φ Ψ Ω

4.1Categories inside categories and set-categories

You can use categories inside categories, as long as the referenced category has previously been defined. For example:

@categories.distribution = flat

categories:

L = aa, ii, ee, oo

V = a, i, e, o, LIn the example above, V has a 20% chance of being a long vowel.

You can also enclose a set of graphemes in curly braces { and }. This is called a 'set-category'. This set will be treated as if it were a reference to a category in terms of frequency. For example, we could write the same example as this:

@categories.distribution = flat

categories:

V = a, i, e, o, {aa, ii, ee, oo}Assigning weights to categories in categories and set-categories is possible.

Categories inside categories and set-categories CANNOT be a part of any sequence. for example C = Xz or C = x{c, d} or C = {a, b}{c, d} will not give the results you might want. To get sequence-like behaviour like that, you will need to use units.

4.2Null grapheme

If a word is built using the syntax character ^, it will disappear in the generated word. In other words ^ is a null grapheme. If you want to use ^ as a grapheme, you will need to escape it. To use other syntax characters as graphemes, they must be escaped too.

5Building words

5.1Words

The words directive defines a set of 'word-shapes' that Vocabug will choose from to create words. A word-shape can consist of individual graphemes, categories, units or a mixture of both.

Word-shapes are separated by a comma, space, or a newline.

By default, words are selected using the Zipf distribution. The first word-shape will be chosen the most often, then the second word-shape the second most often and so on. You can change this distribution. Below is a very simple example that will generate words with one to three CV syllables:

:

C = t, n, k, m, l, s, r, d, h, w, b, j, p, g

V = a, i, o, e, u

words:

CV,CVCV

, CVCVCV,

; This is a commentV

5.2Units

Units are a system that provides an abbreviation of parts of a word-shape. Typically you use it to define the shape of a syllable. Units are defined similarly to categories, but with several important differences:

- Every unit's key is a series of characters that are lowercase a to z, uppercase A to Z,

$,+and- - Units are evoked in the

wordsdirective or inside another unit inside angle brackets<and>. - Units are not sets like categories are.

$ = a, b, cwill not work as you might expect (because as already stated, units are abbreviation for word-shapes). You would need to use a pick-one-set, i.e:<M> = {a, b, c}

For example you could write the last example like so:

:

C = t, n, k, m, l, s, r, d, h, w, b, j, p, g

V = a, i, o, e, u

units:

$ = CVVowel-only = V words

:

<$><$>, <$>, <$><$><$>, <Vowel-only>You can put units inside units. For example: Example = $$

5.3Pick-one-set

A pick-one-set is a group of graphemes and categories separated by spaces or commas, enclosed in curly braces { and }. Vocabug will pick an option from that pick-one just like it would from a unit. For example:

:

V = a, u

words:

t{V, x}This will produce either ta, tu or tx.

Pick-one-sets can be nested inside each other.

Anything inside the pick-one can be assigned a weight, and a pick-one itself can be assigned a weight as well if it is nested inside another set:

:

{a*1, b*2, {c, d}*2}5.4Optional-set

Using round brackets, ( and ), optional-set works the same way as pick-one-set, the only difference is that what's inside them can either appear in the word or not. The probability of each of these variants is 10% by default.

:

ta(n, t, l)In the above example, there is a 10% chance of getting one of tan, tat or tal, but a 90% chance of ta.

5.4.1Optionals weight

By default, an optional-set has a 10% chance of being included in the word. You can change this probability with a decorator.

@words.optionals-weight = 10%words:example

5.5Supra-set

A 'supra-set', is applied over the entire word, and there can only be one supra set. Square brackets [ and ], denotes each item in the supra-set and their location in the word. The items of a supra-set can only be a category, or the null grapheme ^. Only one item in the supra-set will be picked for that generated word.

Supra-set is a feature designed to help generate words with stress systems, pitch accent systems, or other word-based suprasegmentals. Here is an example where it is used for a stress system:

categories:

C = tV = a

X = ' words

:

([X]CV)[X]CVThis produces any of the following words: 'ta, ta'ta, 'tata, never any words with more than one '. Notice here that ta is not possible -- A supra-set item is only chosen after dealing with any sets that the supra-set items are nested in.

5.5.1Supra-set weight

You can set the weights of supra-set items like so:

categories:

R = r

units:

X = o[R*8]Y = e[R*2] words

:

<X><Y>The above example has an 80% chance of generating ore and a 20% chance of generating oer.

Supra-set item weights support a sentinel value -- a 'super-heavy' value s. This s will ensure the supra-set item attached to this weight is always chosen over others. For example: [V*s]

5.6Default distributions

The ordering of items matters in categories, units and word-shapes. The first item will be chosen the most often, the second grapheme the second most often, and so on.

You can change these default distributions (another name for this might be "default drop-off", but I digress). For categories, the default is gusein-zade and you change it with the @categories.distribution decorator. For the separate decorator for word-shapes, the default is zipfian and you change it with the @words.distribution decorator. The distribution will be applied to each item in a set, and then recursively to any set that set is nested in (treating the nested set as an item), then applied at the surface level.

The values of the property distribution can be either:

- A

zipfiandistribution approximates natural language frequency for words, where the highest-ranked item receives the greatest weight, and subsequent ones decay steeply until flattening out. - A

gusein-zadedistribution offers a gentler slope that is natural across phonemes in a language, following a logarithmic decay that still prioritizes top-ranked items but spreads weight more evenly Shallowdistribution, the red-headed step-child of the distributions. It doesn't occur in natural linguistics, but offers us something between Flat and Gusein-Zade. It is Zipfian in nature, a 'long-tailed Zipfian distribution'- A

flatdistribution treats all items equally. This is not to say the items will be evenly chosen -- items are still being randomly chosen on a generation, they just have uniform weights

5.7Assigning weights

If you want to set your own frequency for graphemes in a category or category-set, items in a pick-one-set, or optional-set, or word-shapes in the words directive, you can use an asterisk * to specify the weight for each item, like so:

:

V = a*5, e*4, i*3, o*2, u*1

units:

$ = {V*8, x*2}

words:

<$>*2, yV has approximately the following probabilities: a: 33%, e: 27%, i: 20%, o: 13%, u: 7%. The pick-one-set in the $ unit has an 80% chance of producing a V category over the x grapheme. And the first word-shape in the words directive has twice the chance of being chosen over the next word-shape.

As you might have noticed in the example above, in a sequence that has at least one weighted option, it overwrites any default distributions. Also important to note is that any other option that you had not given a weight (inside that set, or on the surface level), is given a weight of 1.

6The alphabet directive

The alphabet directive gives provides a custom alphabetisation order for words, when the sort words checkbox is selected.

:

a, b, c, e, f, h, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, p', r, s, t, t', yThis would order generated words like so: cat, chat, cumin, frog, tray, t'a, yanny

7The invisible directive

Sometimes you will want characters, such as syllable dividers, to be invisible to alphabetisation order. You can do this by listing these characters in the invisible directive.

:

., ' This will make these generated words: za'ta, 'ba.ta, 'za.ta be reordered into: 'ba.ta, za'ta, 'za.ta

8The graphemes directive

The graphemes directive dictates which (multi)graphs, including character + combining diacritics, are to be treated as grapheme units when using transformations.

:

a, b, c, ch, e, f, h, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, p', r, s, t, t', yIn the above example, we defined ch as a grapheme. This would stop a rule such as c -> g changing the word chat into ghat, but it will make cobra change into gobra.

Which graphemes are 'associatemes' of their 'bases' are declared in the graphemes directive. Read more about this in this section of the documentation.

9The stage directive

Once words are generated, you might want to modify them to prevent certain sequences, outright reject certain words, or simulate historical sound changes. This is the purpose of transforms, which are all declared in the stage directive:

:

; Your transforms go hereThe default transform is a rule. These should be familiar to anyone who knows a little about phonological rules. The two other types of transforms are cluster-fields and routines.

A rule can be summarised as four fields: CHANGE / CONDITION ! EXCEPTION. The characters / and ! that precede each field (except for the CHANGE) are necessary for signalling each field. For example, including a ! will signal that this rule contains an exception, and all text following it until the next field marker will be interpreted as such.

Every rule begins on a new line and must contain a CHANGE. The CONDITION or EXCEPTION fields are optional.

If you want to capture graphemes that are normally syntax characters in transforms, you will need to escape them.

When this document uses examples to explain transformations, the last comment shows an example word transforming. For example ; amda ==> ampa means the rule will transform the word amda into ampa

9.1Naming stages

Using a decorator on a stage, you can name that stage. In debug mode, the name of the stage will be printed out when each word is being processed on that stage.

@stage.name = My Transform Stage

stage:

; Your transforms go here10The change

The format of a rule's CHANGE can be expressed as TARGET -> REPLACEMENT.

TARGETspecifies which part of the word is being changed- Then followed by hyphen and greater-than-sign

->.->can be swapped with either>>,=>,⇒or→if you prefer REPLACEMENTis whatTARGETis changing into, or in other words, replacing

Let's look at a simple unconditional rule:

o -> x

; bodido ==> bxdidx

In this rule, we see every instance of o become x.

10.1Concurrent change

Concurrent change is achieved by listing multiple graphemes in TARGET separated by commas, and listing the same amount of replacement graphemes in REPLACEMENT separated by commas. Changes in a concurrent change execute at the same time:

o, a -> a, o

; boda ==> bado

Notice that the above example is different to the example below:

a -> o

; boda ==> bodo

Where each change is on its own line, o merges with a, then a becomes o.

10.2Merging change

Instead of listing each REPLACEMENT in a concurrent change, we can instead list just one that all the TARGETs will merge into:

o, a -> x

; boda ==> bxdx

This is equivalent to:

o, a -> x, x

; boda ==> bxdx

10.3Reject

To remove, or in other words, reject a word, you use a zero 0 in REPLACEMENT:

In the above example, any word that contains a or bi will be rejected.

11Insertion and deletion

Insertion requires a condition to be present, and for a caret ^ to be present in TARGET, representing nothing.

Deletion happens when ^ is present in REPLACEMENT:

12The condition

Conditions follow the change and are placed after a forward slash. When a transform has a condition, the target must meet the environment described in the condition to execute.

The format of a condition is / BEFORE_AFTER

- A forward slash

/begins a condition BEFOREis anything in the word before the target- The underscore

_is a reference to the target in a condition AFTERis anything in the word after the target

For example:

o -> x / p_p

; opoptot ==> opxptot

12.1Multiple conditions in one rule

Multiple conditions for a single rule can be made by separating each condition with additional forward slashes. The change will happen if it meets either, or both of the conditions:

o -> x / p_p / t_t

; opoptot ==> opxptxt

12.2Word boundary

Hash # matches to word boundaries. Either the beginning of the word if it is in BEFORE, or the end of the word if it is in AFTER

; opoppop ==> opoppxp

12.3Syllable boundary

Dollar-sign $ matches to either the character ., to any of the syllable-divider graphemes stated in the syllable-boundary directive, or if no match, tries to match word boundaries. Either the beginning of the word if it is in BEFORE, or the end of the word if it is in AFTER

; o.pop.pop ==> o.pxp.pxp

12.3.1Syllable boundaries directive

The syllable-boundaries directive lets you define which graphemes are to be treated as a syllable-boundary:

:

., '

stage:

o -> x / p_p$; o.pop'pop ==> o.pxp'pxp

13The exception

Exceptions are placed following an exclamation mark ! and go after the condition, if there is one. Exceptions function exactly like the opposite of the condition -- when a rule has an exception, the target must meet the environment described in the exception to prevent execution:

In the above example, the transformation will not execute if aa is at the end of the word.

If there are multiple exceptions, the transform must meet all of the exceptions for it not to execute.

An alternative to using an exclamation mark is to use two forward slashes //.

14Alternator and Optionalator

These are sets just like the sets in word-creation, but they cannot be nested.

14.1Alternator-set

Enclosed in curly braces, { and }, only one Item in an alternator set will be part of each sequence. For example:

The above example is equivalent to:

These can also be used in exceptions and conditions:

14.2Optionalator-set

Items in an optionalator, enclosed in ( and ) can be captured whether or not they appear as part of a grapheme or as part of a sequence of graphemes:

x(w) -> k

; xwaxaħa ==> kakaħa

Optional-set can also attach to an alternator-set:

{x, ħ}(w) -> k

; xwaxaħa ==> kakaka

Optionalator-set cannot be used on its own, it must be connected to other content.

15Using categories

You can reference categories in transforms. The category will behave in the same way as an alternator set:

stage:

B -> ^

; xapay ==> apaIf the category is inside a set, it MUST be listed as an item on its own:

; xvayazv ==> ayaThis is to say {Bz}v -> ^ is invalid.

16Features

Let's say you had the grapheme, or rather, phoneme /i/ and wanted to capture it by its distinctive vowel features, +high, -round and +front, and turn it into a phoneme marked with +high, -round and +back features, perhaps /ɯ/. The features directive and feature matrices let you do this. The features can be described as binary and 'fully-specified'.

The key of all features must consist of lowercase letters a to z, uppercase letters a to z, ., - or +

16.1Pro-feature

A feature prepended with a plus sign + is a 'pro-feature'. For example +voice. We can define a set of graphemes that are marked by this feature by using this pro-feature. For example:

16.2Anti-feature

A feature prepended with a minus sign - is an 'anti-feature'. For example -voice. We can define a set of graphemes that are marked by a lack of this feature by using this anti-feature. For example:

16.3Para-feature

A feature prepended with a greater-than-sign > is a 'para-feature'. A para-feature is simply a pro-feature where the graphemes marked as the anti-feature of this feature are the graphemes in the graphemes: directive that are not not marked by this para-feature:

Is equivalent to the below example:

-vowel = b, h, k, n, t

'Where does this leave graphemes that are not marked by either the pro-feature or the anti-feature of a feature?', you might ask. Such graphemes are unmarked by that feature.

16.4Referencing features inside features

Features can be referenced inside features. For example:

+non-yod = +vowel, ^i

Use a caret in front of a grapheme to ensure that that grapheme is not part of the pro/anti/para-feature. In the example above, the pro-feature '+non-yod' is composed of the graphemes a and o -- the grapheme i is not part of this pro-feature. Due to the recursive nature of nested features, this removed grapheme will be removed... aggressively. For example, If +non-yod were to be referenced in a different feature, that feature would always not have i as a grapheme.

16.5Using Features

To capture graphemes that are marked by features in a transform, the features must be listed in a 'feature-matrix' surrounded by [ and ]. The graphemes in a word must be marked by each pro-/anti-feature in the feature-matrix to be captured. For example if a feature-matrix [+high, +back] captures the graphemes: u, ɯ, another feature-matrix [+high, +back, -round] would capture ɯ only.

The very simple example below is written to change all voiceless graphemes that have a voiced counterpart into their voiced counterparts:

In this rule, in REPLACEMENT, [+voice] has a symmetrical one-to-one change of graphemes from the graphemes in [-voice] in TARGET, leading to a concurrent change. Let's quickly imagine a scenario where the only [+voice] grapheme was b. The result will be a merging of all -voice graphemes into b: tamepfa ==> bamebba.

It should be noted that feature-matrices in TARGET have no carryover to feature-matrices in REPLACEMENT. For example, in a bogus rule such as o -> [+high] the program will not try to transform <o> into it's [+high] counterpart, it will try and replace <o> with some grapheme marked as [+high] and will probably fail unless only one grapheme is marked as [+high].

If the category is inside a set, it MUST be listed as an item on its own:

[+example], z}v -> ^; xvayazv ==> ayaThis is to say {[+voiced]z}v -> ^ is invalid.

16.6The feature-field directive

Feature-fields allow graphemes to be easily marked by multiple features in table format.

The graphemes being marked by the features are listed on the first row. The features are listed in the first column.

For example:

feature-field:

m n p b t d k g s h l j

voice + + - + - + - + - - + +

plosive - - + + + + + + - - - -

nasal + + - - - - - - - - - -

fricative - - - - - - - - + + - -

approx - - - - - - - - - - + +

labial + - + + - - - - - - - -

alveolar - + - - + + - - + - + -

palatal - - - - - - - - - - - +

velar - - - - - - + + - - - -

glottal - - - - - - - - - + - -

feature-field:

a e i o

high - - + -

mid - + - +

low + - - -

front - + + -

back + - - +

round - - - +- A

+means to mark the grapheme by that feature's pro-feature - A

-means to mark the grapheme by that feature's anti-feature - A

.means to leave the grapheme unmarked by that feature

Here are some matrices of these features and which graphemes they would capture:

[+plosive]captures the graphemesb, d, g, p, t, k[+voiced, +plosive]captures the graphemesb, d, g[+voiced, +labial, +plosive]captures the graphemeb

17Wildcards and quantifiers

Wildcards and the like in this section are special tokens that can represent arbitrary amounts of arbitrary graphemes, which is especially useful when you don't know precisely how many, or of what kind of grapheme there will be between two target graphemes in a word.

17.1Quantifier

Quantifier, using +, will match once or as many times as possible to the grapheme to the left of it. Quantifier cannot be used in REPLACEMENT:

; raraaaaa ==> roro17.2Bounded quantifier

The bounded quantifier matches as many times its digit(s), enclosed in ?[ and ], to the things to the left.

o -> x / r?[3]_

; ororrro ==> ororrrxThe digits in the quantifier can also be a range:

o?[2,4] -> x

; tootooooo ==> txtxoAt the beginning of the list, , represents all the possible numbers lower than the number to the right, not including zero.

o?[,4] -> x

; tootooooo ==> txtxAnd finally at the end of the list, , represents all possible numbers larger than the number to the the left

o?[4,] -> x

; toootooooo ==> toootxA bounded quantifier can be used in REPLACEMENT as long as there is a definite maximum quantity. Or in other words, you cannot produce an infinite amount of something!

17.3Ditto-mark

Ditto-mark using colon :, will duplicate the grapheme, or grapheme from a set or category, to the left of it. In other words, you can capture an item only when it is doubled using the ditto-mark:

; aaata => oataA ditto-mark can be used in REPLACEMENT:

; tat => taat17.4Wildcard

Wildcard, using asterisk *, will match once to any grapheme. Wildcard does not match word boundaries. Wildcard cannot be used in REPLACEMENT:

; Any grapheme becomes <x> when any grapheme follows it* -> x / _*

; aomp ==> xxxpWildcard can be placed by itself inside an optionalator (*), thereby allowing it to match nothing as well.

17.5Anythings-mark

The anythings-mark uses percent sign % and a pair of square brackets [ and ]. It will match as many (but not zero) times to any grapheme. For example:

; abitto => axAs we can see, the rule matched b and greedily matched every and any grapheme after it.

The example below uses an anythings-mark in the condition:

a, i, u -> ã, ĩ, ũ / {ã, ĩ, ũ}%[]_

; pabãdruliga ==> pabãdrũlĩgã

17.5.1Laziness and cowardliness

By listing graphemes and grapheme sequences inside the square brackets, we can alter the "greedy" behaviour of an anythings-mark with degrees of "laziness" and 'cowardliness'.

Consuming negative lookahead, AKA "laziness":

Sometimes it is necessary to for the anythings mark to consume graphemes we are monitoring for, and then stop consuming:

; babitto => xtoAs we can see, the rule matched b followed by anything else until it reached the first t, consumed that, then stopped matching. This behaviour in Regular Expression terminology is called "lazy".

As already stated, the items to check for greediness can be a sequence of graphemes:

; batitro => xoSets, categories and features can also be used when monitoring for laziness and cowardliness:

Negative lookahead, AKA 'cowardliness':

Sometimes it is necessary for graphemes to block the spread without having them be consumed, which I have dubbed 'cowardliness'. To do this put a pipe | after the lazy items and list the cowardly items. For example we might want the graphemes k or g to prevent the rightward spread of nasal vowels to non nasal vowels:

; pabãdruliga ==> pabãdrũlĩga

18Cluster-field

Cluster-field is a way to target sequences of graphemes and change them. They are laid out as tables, and start with < followed by a space. The first part of a sequence is in the first column, and the second part is in the first row. The clusterfield ends with a > on its own line. For example:

- In this example,

npbecomes mp andmtbecomes nt - These are executed concurrently just like concurrent changes. Their order does not matter

+means to not change the target cluster at all- Cluster-fields can use

0to reject the word if it contains that sequence - Cluster-fields can use

^to delete the target sequence

19Advanced

This is the advanced section. It presents solutions to edge-cases and novel systems to achieve the desired forms of words.

19.1Routine

The routine transform provides useful functions that you can call at any point in the transform block. You call a routine on a newline with <routine, optional space, =, optional space, the routine, and a closing >.

The routines are:

decomposewill break-down all characters in a word into their "Unicode Normalization, Canonical Decomposition" form. For example,ñas a singular unicode entity, \u00F1, will be broken-down into a sequence of two characters, \u006E + \u0303composedoes the opposite of decompose. It converts all characters in a word to the "Unicode Normalization, Canonical Decomposition followed by Canonical Composition" form. For example,ñas two characters \u006E + \u0303, will be transformed into one character, \u00F1capitalisewill convert the first character of a word to uppercasedecapitalisewill convert the first character of a word to lowercaseto-uppercasewill convert all characters of a word to uppercaseto-lowercasewill convert all characters of a word to lowercasereversewill reverse the order of graphemes in a wordxsampa-to-ipawill convert characters of a word written in X-Sampa into IPA.ipa-to-xsampawill convert them backReveal

IPA to / from X-SAMPA X-SAMPA IPA b_< ɓ d_< ɗ d` ɖ g_< ɠ h\ ɦ j\ ʝ l\ ɺ l` ɭ n` ɳ p\ ɸ r\ ɹ r\` ɻ r` ɽ s\ ɕ s` ʂ t` ʈ x\ ɧ z\ ʑ z` ʐ A ɑ B β B\ ʙ C ç D ð E ɛ F ɱ G ɣ G\ ɢ G\_< ʛ H ɥ H\ ʜ I ɪ J ɲ J\ ɟ J\_< ʄ K ɬ K\ ɮ L ʎ L\ ʟ M ɯ M\ ɰ N ŋ N\ ɴ O ɔ O\ ʘ v\ ʋ P ʋ Q ɒ R ʁ R\ ʀ S ʃ T θ U ʊ V ʌ W ʍ X χ X\ ħ Y ʏ Z ʒ " ˈ◌ % ˌ◌ : ◌ː :\ ◌ˑ @ ə @\ ɘ @` ɚ { æ } ʉ 1 ɨ 2 ø 3 ɜ 3\ ɞ 4 ɾ 5 ɫ 6 ɐ 7 ɤ 8 ɵ 9 œ & ɶ ? ʔ ?\ ʕ <\ ʢ >\ ʡ ^ ꜛ ! ꜜ !\ ǃ | | |\ ǀ || ‖ |\\|\ ǁ =\ ǂ -\ ‿ latin-to-hangulconverts, or rather, transliterates characters written in an arbitrary romanisation into Hangul Jamo blocks.hangul-to-latinconverts them back.Reveal

Initial and final jamo A romanisation Initial Final k ㄱ ㄱ gk ㄲ ㄲ n ㄴ ㄴ t ㄷ ㄷ dt ㄸ r ㄹ ㄹ m ㅁ ㅁ p ㅂ ㅂ bp ㅃ s ㅅ ㅅ z ㅆ ㅆ c ㅈ ㅈ j ㅉ ch ㅊ ㅊ kh ㅋ ㅋ th ㅌ ㅌ ph ㅍ ㅍ x ㅎ ㅎ gn ㅇ Medial jamo A romanisation Hangul a ㅏ ẹ ㅐ ọ ㅓ e ㅔ o ㅗ u ㅜ ụ ㅡ i ㅣ wa ㅘ wẹ ㅙ wọ ㅝ we ㅞ wi ㅚ uí ㅟ ụí ㅢ ya ㅑ yẹ ㅒ yọ ㅕ ye ㅖ yo ㅛ yu ㅠ When there is no initial to be found, the jamo will have an initial Ieung. Forming an initial of the next jamo is preferred over creating a final for the current jamo

latin-to-greekconverts, or rather, transliterates characters written in an arbitrary romanisation into greek letters.greek-to-latinconverts them backReveal

Greek to / from Latin Latin Greek a α á ά à ὰ e ε é έ è ὲ ẹ η ẹ́ ή ẹ̀ ὴ i ι í ί ì ὶ o ο ó ό ò ὸ ọ ω ọ́ ώ ọ̀ ὼ u υ ú ύ ù ὺ b β d δ f φ g γ k κ l λ m μ n ν p π r ρ s σ t τ x χ z ζ q ξ þ θ ṕ ψ c ϛ č ͷ h ͱ j ϳ š ϸ w ϝ

21.2Target-mark

A target-mark is a reference to the captured TARGET graphemes. It cannot be used in TARGET. This uses an ampersand and a capital t &T.

Here are some examples where target-mark is employed:

Full reduplication:

"Haplology":

Reject a word when a word-initial consonant is identical to the next consonant:

19.3Metathesis-mark

Simple metathesis involves an ampersand and a capital m &M in REPLACEMENT. This will swap the first and last grapheme from the captured TARGET graphemes:

; apma ==> ampa

Since metathesis reference is swapping the first and last grapheme, we can effectively simulate long-distance metathesis using an anythings-mark:

; parabla ==> palabra

19.4Empty-mark

An Empty-mark using &E, inserts an 'empty' grapheme into the captured TARGET graphemes. It is only allowed in TARGET

One use for it is a trick to make one-place long-distance metathesis work, for example:

19.5Reference

Sometimes graphemes must be copied or asserted to be a certain grapheme between other graphemes. This is the purpose of 'reference'. Reference is fairly straightforward, but there is a lot of jargon and different behaviour between fields to explain.

19.5.1Reference of singular grapheme

A grapheme (or graphemes) are bound to a reference using a 'reference-capture', to the right of some grapheme. A reference-capture looks like = followed by a single-digit positive number. This number is called the 'reference-key' of the reference. The grapheme (or graphemes) bound to the reference is called the 'reference-value'.

The key behaviours of reference-capture are:

- If there are no graphemes to be captured by the reference-capture, nothing is captured

- A Reference forgets its reference-value in-between rules. References do not persist between rules

- You can have up to nine references per rule

- A reference's reference-value can be overwritten with a new reference-capture

- For reference-capture in conditions, a grapheme is captured only if that condition is met

The captured grapheme can then be reproduced elsewhere in the rule with a 'reference-mark', even before the reference-capture. The reference-mark invokes the reference-key of a reference.

The key behaviours of reference-mark are:

- A reference-mark may not be used in the

TARGETof a rule. - In each condition or exception of a rule, a reference-mark cannot be used before content has been bound to its reference with a reference-capture. For example

a -> e / 1x=1_is invalid, and so isa -> e / 1_x=1. Reference is not recursive in conditions and exceptions. - If a reference-mark is used where a reference-capture has not captured anything yet, it fails silently and outputs the number of the backrefence.

Here are some examples:

In the rule above, we are binding the [+vowel] feature-matrix to the reference 1, by appending =1 to it. Whatever this grapheme from [+vowel] is when the condition is met, is captured as the value of 1. Then the value of backrefence 1 is in AFTER by invoking its reference-mark.

In the rule above, we are binding the [+vowel] feature-matrix to the reference 1, by appending =1 to it. Whatever this grapheme from [+vowel] is when the condition is met is the value of 1. Then the value of 1 is inserted into REPLACEMENT by invoking its reference-mark.

19.5.2Reference of grapheme sequence

Now that 'reference-capture' and 'reference-mark' has been (hopefully) introduced and explained adequately, let's explain how to capture and reference a sequence of graphemes.

To start capturing a sequence, you use a 'start-reference-capture', &= before the graphmemes to be captured. Then at the end of the graphemes to be captured, a 'reference-capture' is used to bind those graphemes to a reference:

19.6Associatemes

If your language encodes tone, stress, breathy voice, or other phonological features directly on vowels, you'll often need to target a particular grapheme across its variants.

One method is to target each variant manually:

; daná ==> dené

This workaround uses alternators, but lacks semantic clarity and scalability, and is outright tedious.

To solve this, are 'associatemes' -- aligned variant graphemes associated with their base grapheme, and other associated graphemes -- other SCAs might use the terms "floating diacritics" or "autosegmentals". These allow you to target all forms of a grapheme with a single token. To set up associatemes, they must be stated in the graphemes directive with the base associateme set of an entry inside curly braces, and each variant set in curly braces with a < to the left of the base set, or another variant set, like so:

The behaviour of associatemes are:

- Each grouping must contain an equal number of graphemes, aligned by position. This creates a traceable overlay across tone, stress, and other features

- This does not mean that each variant must be different by means of diacritics, they are arbitrarily variant. For example

{a,b,c}<{x,y,z}is valid - This does not mean that we can have only one grouping set. For example

{a,i,o}<{á,í,ó}, {a,b,c}<{x,y,z}is valid

In a rule, you then put a tilde after the grapheme to mark it as a base associateme. This is called a 'based-mark'. For example:

; daná ==> dené

This transform targets all variants of a and carries over that association to e.

19.7Letter case field

This program can change the case of letters or the whole word with routines or with paragraph mode. However your language may not have the expected correspondences between lowercase and uppercase. Some examples:

Turkish: The lowercase i becomes uppercase İ, and the uppercase I becomes lowercase ı.

Some polynesian languages: The vowel after an "okina" is capitalised instead of the okina itself.

Some styles in a few European languages: Sometimes both letters of a digraph will be capitalised.

To accommodate these special cases, you can define a letter case field directive. For example:

20Blocks

Blocks modify the behaviour of transforms that are inside them with 'condition and event' logic.

They begin with a <@ at the beginning of a line, and end with a > on the beginning of a line.

20.1Chance block

This block will indicate a chance that the transformations inside the block will occur or not. They cannot be nested. This is useful for sporadic sound change.

The above example's transforms have a 60% chance of occuring on each word.

21Questions and answers

Here are some common questions and answers about Vocabug:

The Generate button is greyed out

This means Vocabug is busy generating words for you, and will eventually become clickable again. If you think this is taking too long, perhaps you have force word limit accidentally on.

I received the error "Invalid regular expression"

This error occurs because you are using Vocabug in an old browser or old browser version that does not support lookbehind. You can check if this applies to you here.

What is a natural frequency for consonants in a language?

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to this question, and different analyses of word lists may produce different data on what the general expectation is. For example, in English, /ð/ is very uncommon among all the words in English, however it is a common phoneme among sentences because of the prevalence of the words this, that, those and the. And indeed, morphology, historical sound changes and word borrowing can skew any initial control you might have over frequencies.

However, a good rule of thumb is that phonemes that are easy to pronounce and distinguish will be the most common.

How do I weight an individual optional-set?

Using the @words.optionals-weight decorator affects the weight of all optional-sets. As of version 1, there is no direct way to weight an individual optional-set. You can however, use ^ as an item in an alternator, like a{b, c, ^*3}